THE CLOTHING RESTORATION PROJECT

BLOG 002

11.03.2023

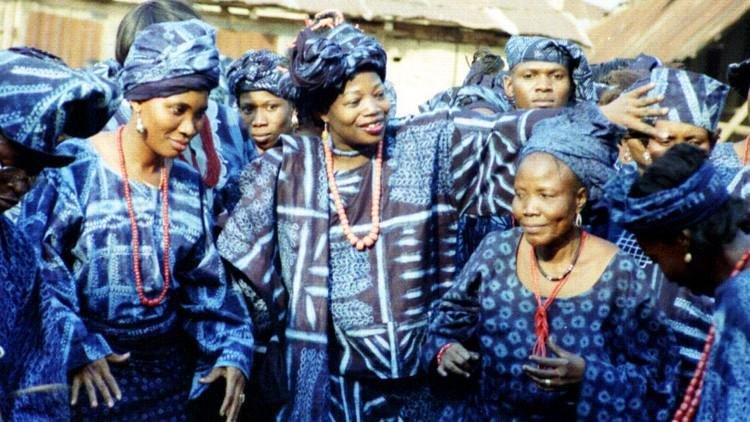

West African Women as Masters of Indigo

The forests gave way before them, and extensive verdant elders, richly clothed with produce, rose up as by magic before these hardy sons [and daughters] of toil…. Being farmers, mechanics, laborers and traders in their own country, they required little or no instruction in these various pursuits.

—Martin Delany, The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States (1852)

In January 2023, the Clothing Restoration Project team traveled to visit Nadia Adanle at Couleur Indigo in Ouidah, Benin (formerly Dahomey). Throughout our travels, we continuously heard that the age-old tradition of indigo dyeing in West Africa was disappearing. We discovered Nadia’s work in contributing to the revival of the dyeing tradition through our field researcher, Titi Gakoto.

Our goal was to learn more about Nadia’s work at Couleur Indigo and to discover how she has played a key role in the revitalization of native indigo cultivation and dyeing techniques in Benin. What we learned encompasses a rich narrative history on the role of women in West African indigo mastery that took us from Ouidah, Benin to the Americas.

Image source: mapsofindia.com

What is Couleur Indigo?

Nadia Adanle; Source: Coloeur Indigo

Couleur indigo was established by Nadia in 2007 to restore ancestral natural indigo dyeing and textiles, practices inherited from a distinct family of Anyabusu women who she credits as masters of the indigo dyeing tradition in Benin. Before starting Couleur Indigo, Nadia studied for a decade under the last three remaining Anyabusu women alive who held the knowledge and craftsmanship of Yoruba and Benin indigo dyeing techniques.

Bringing traditional indigo dyeing back to Benin involved learning every step of the dye and textile manufacturing process. Today, Couleur Indigo cultivates and processes native Indigo/Èlú (Philenoptera cyanescens) to use in dyeing textiles woven from locally sourced organic cotton, which is also sewn into ready-to-wear clothing. Another component of Couleur Indigo’s business is a line of various items including wallets, hats, and home decor made from their textile scraps to ensure a zero-waste production process at their factory.

““Through our factory, we are preserving the tradition with a pinch of modernity and paying tribute to our culture and the environment,“ Nadia shared. “Today, this process starts at our farm where we are producing the leaves and goes all the way to our showroom where our fabrics are exhibited.””

Honoring the History of Indigo Production in West Africa

Over the last fifteen years, Nadia has centered the expertise of West African women indigo practitioners and their contributions to global economic power in pre-colonial West Africa. Her own indigo journey began with veteran women indigo masters in Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso) and Cotonou (Benin) before she established the Couleur Indigo factory and store in Ouidah in September 2020. She chose Ouidah as the location for the factory because of its commercial history as a women-led indigo production site as well as its role in the transatlantic slave trade.

As Nadia tells us, “Ouidah was a large place for slavery in West Africa and we try to share our own history with slavery and indigo at Couleur Indigo.”

Ouidah’s prime location next to the water and sophisticated trade networks with interior West African kingdoms played a significant role in the economic development of the region.

“If you look at the geography of Ouidah, it is like an island. There is water and lakes on every side,” said Nadia.

Ouidah was also a tributary state to the Oyo Empire, Yoruba’s ruling elite, and was one of the most politically and culturally important states in Western Africa from the mid-17th to the late 18th century. According toNadia, during this period Ouidah was popularly known for its indigo production and credits Yoruba women for sharing their expertise with the Anyabusi women. To emphasize this relationship, she told us that in Ouidah, indigo is called by its Yoruba name èlú as a way to honor the Yoruba women originally from Abẹ́òkúta who were masters of indigo dyeing and taught the techniques to women in Ouidah. She also insists that using èlú instead of the word indigo is a rejection of colonialism

Further investigation on our end led to research by Stephen Hamilton tilted Alaro: Indigo and the Power of Women in Yorubaland which states:

“Some of the earliest European descriptions of Yorubaland describe extensive indigo processing practiced by female specialists. Explorer Hugh Clapperton describes the town Ijana in 1825 as having “upwards of twenty vats per house,” “women were the dyers,” and that “the indigo here is excellent and forms the most capital dye” (Lockhart and Lovejoy, 2005; Ogundiran, 2009). As we see from both archeological and eyewitness reports, indigo has a long history in southern Nigeria. Eyewitness reports in Yorubaland from almost 200 years ago attest to this craft being sophisticated, widespread, and female-dominated.”

The expertise of women indigo masters in Ouidah contributed to the high quality and desirability of indigo produced in the region. Their knowledge, skill and craftsmanship with indigo dye elevated the reputation of Ouidah as a center for indigo production. As a result, increased competition for trade along the West African Coast resulted in the French, English, Dutch, and Portuguese traders constructing their own forts to tap into Ouidah’s growing markets by transporting millions of masters of the craft, many of them women, into the Americas to exploit their skills and mastery of the craft. These enslaved Africans with expertise in Indigo production were spread throughout the Caribbean, and the North American mainland.

By the late 1600s thousands of enslaved Africans populated the Caribbean Islands clearing forests for the cultivation and processing of indigo for export. From 1671 to 1684, the number of indigo plantations increased from nineteen to forty in Jamaica alone. In North America, indigo was South Carolina’s second largest export, with 87,415 pounds being shipped from Charleston between November 1749 and November 1750. During the second half of the eighteenth century, indigo production expanded substantially, remaining Carolina’s second-most important export, after rice. (Knight, 2010). Today, little is remembered of the indigo masters forced into slavery in the Americas and their contribution to modern industry.

Nadia’s vision is to correct the erasure of these indigo masters in conversations about indigo and to remind us that the tradition disappeared in West Africa largely due to the impact of the transatlantic slave trade, and the forced removal of skilled masters from their homes and communities.

Source: Triumph Magazine

The Future of Indigo in West Africa

Showing a resist-dye design called “marinière”

Nadia sees her work at Couleur Indigo as impactful because the story of her ancestors does not end with the trauma of slavery. Instead, she chooses to honor and preserve the centuries old tradition by making it accessible to the younger generation, both through keeping dyeing practices and education alive and through creating new vocations. The proliferation of chemical dyes and textile waste seen in modern industrial indigo clothing production is antithesis to traditional West African lifestyle and culture. Her motivation is to demonstrate a more environmentally-friendly method for dyeing that is steeped in tradition and honors West African history and culture while ensuring “a touch of modernity.”

Showing a resist-dye design called “aṣọ fenu”. Aṣọ is the Yoruba word for “cloth” and fenu means “precious”.

We are grateful to Nadia Adanle for her generosity. She gave us a tour of Couleur Indigo which we are happy to share with you. You can learn more Couleur Indigo here.

Sources:

Delany, Martin Robison. The condition, elevation, emigration, and destiny of the colored people of the United States. Black Classic Press, 1993.

Hamilton, Stephen. “The Art of Stephen Hamilton.” Itan Project: The Art of Stephen Hamilton, 2016, www.itanproject.com/alaro-indigo-and-the-power-of-women-in-yorubaland-by-stephen-hamilton. Accessed 1 Nov. 2023.

Joseph, Marietta B. “West African Indigo Cloth.” African Arts, vol. 11, no. 2, 1978,

pp. 34–95. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3335446. Accessed 1 Nov. 2023.

Knight, Frederick C. “Working the Diaspora: The Impact of African Labor on the Anglo-American World, 1650-1850.” Choice Reviews Online, vol. 48, no. 03, 1 Nov. 2010, pp. 48–1628, https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.48-1628. Accessed 1 Nov. 2023.